Internet Explorer and Netscape have been at it for a while – they've never entirely been on the same page when it comes to rendering web pages. Indeed, comparing the same web page on both browsers on both Mac and PC can often be like looking at four completely different pages. And this says nothing of the additional issues brought out by UNIX and Mac specific browsers like Opera and Chimera.

Internet Explorer and Netscape have been at it for a while – they've never entirely been on the same page when it comes to rendering web pages. Indeed, comparing the same web page on both browsers on both Mac and PC can often be like looking at four completely different pages. And this says nothing of the additional issues brought out by UNIX and Mac specific browsers like Opera and Chimera.But finally order was returning to the universe. The new generation of Netscape browsers (6.0 and higher) and the current IE browsers had achieved a happy synchronicity. If designed right, web pages could look (relatively) the same on both platforms with both browsers. All was right with the world.

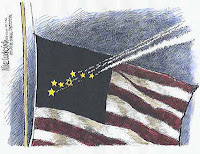

And then came Safari.

Safari is a Mac OSX browser designed to take advantage of the awesome power latent in Apple's most advanced operating system, Jaguar. In the month following Safari release at the January Macworld Conference, the necessity for Safari had been much debated by Mac pundits, Apple marketers, and Joe Shmoes alike. But we have a bigger question: What is this going to do for web design?

We already have to design for two major browsers on two major platforms while considering a handful of tertiary browsers. Is Safari's entry into the market enough to keep us up at night? Certainly, Safari does see things a little differently. In Apple tradition, it renders fonts small but anti-aliased (smooth, onscreen). The browser honors HTML standards and even has a built-in bug-reporting system in the beta release so that users can report everything from application crashes to web pages that appear incorrectly.

But two issues are really at the core of the question: Does it differ significantly from IE and Netscape in how it renders pages and how many people will use it?

The answer first: No. Only in font rendering does Safari differ at all from it's two larger competitors. Safari treats CSS's in it's own way – especially in regard to its treatment of styles associated with form fields – but gets close to the treatment provided by the other two for basic text styles.

The answer second: No. Despite being a solid and extremly usable browser, Safari is likely to remain a small player. That is not to say that it isn't a great browser. Safari features spell checking in form fields, a built-in Google search, the ability to snap back to search results pages, a "smart" pop-up blocker, great cookie control options, advanced bookmark management and importation from IE, address book integration into the bookmarks, a global page history, a download manager, and speed. Safari is much faster at page loading and launching than IE, Netscape, and Chimera. But it is Mac specific and Macs are, unfortunately, the minority. Even if every Mac user switched over to Safari the browser wouldn't enjoy more than 5-10% of the market.

Rare will be the design developed or designer developing exclusively for Safari. It is a great browser (though I know some Chimera advocates who would argue against it at every point). The Apple design team has created the best looking and best running browser on the Mac. When it comes out for PC (if it comes out for PC) a larger conversation will be in order about the future of Internet browser. Until then, I'll keep Safari and IE open on my desktop. fb